For many people, caffeine is a gentle ritual that shapes the rhythm of the day — the warm morning cup that signals a beginning, the mid-afternoon boost that carries you through a slow moment, the comforting sip during a conversation or creative task. Caffeine is woven into emotional, social, and productivity patterns in ways that feel both familiar and effortless.

But the timing of caffeine — not just the amount — has a surprisingly strong influence on how easily your body transitions into evening calm. And this influence often hides in plain sight. People regularly say, “Coffee doesn’t keep me awake”, even as their sleep becomes lighter, more fragmented, or harder to initiate. The absence of jitteriness doesn’t always mean the absence of impact.

Caffeine interacts with the brain through a mechanism that is slow, steady, and long-lasting. Because of this, your “last cup” creates a ripple that stretches deep into the evening — whether or not you feel it. Understanding how caffeine behaves in the body can help you choose a cut-off time that supports rest rather than interferes with it.

This isn’t about restriction. It’s about rhythm.

How caffeine actually works in the brain

To understand cut-off times, we need to understand how caffeine interacts with adenosine, the molecule that builds up during the day and creates feelings of sleep pressure.

Adenosine is like a slow internal timer. The longer you’re awake, the more it accumulates, gently nudging the brain toward rest. Caffeine doesn’t replace adenosine — it blocks its receptors. That means your brain doesn’t feel tired, even if the chemical markers of tiredness are still present. This is why caffeine can feel so clean and effortless. It doesn’t jolt you awake; it simply prevents you from noticing your fatigue.

But there’s a catch: when caffeine wears off, the adenosine that’s been blocked still remains. It “rushes in” all at once, creating what many people know as a caffeine crash. And because adenosine continues to circulate for hours, the blocking effect of caffeine can interfere with sleep long after the stimulating feeling disappears.

This is where the concept of half-life becomes essential.

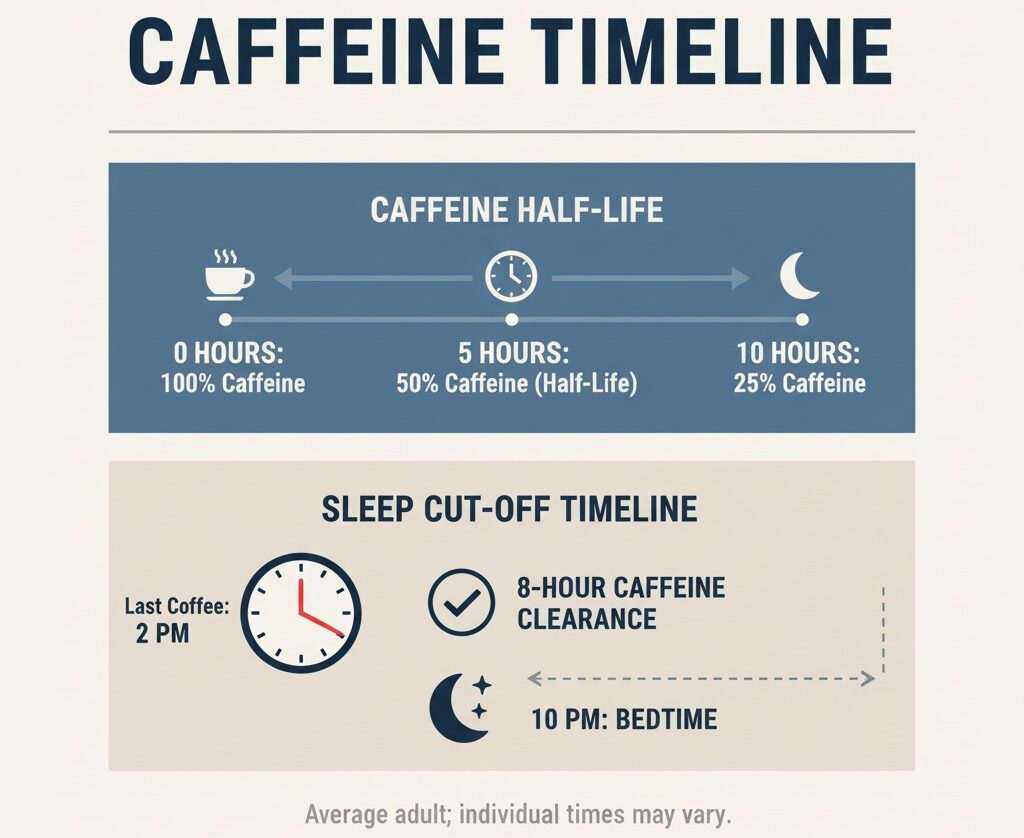

The average half-life of caffeine in healthy adults is around five to six hours — meaning half of what you consumed is still in your system after that time. Some people metabolize caffeine even more slowly, with half-life stretching to eight hours or more.

The Cleveland Clinic notes that caffeine can linger in the system for a surprisingly long time, with measurable effects even after 10–12 hours in some individuals.

This is why cut-off timing matters. Your evening energy is shaped by decisions you made hours earlier.

What research reveals about cut-off times

There’s no single universal caffeine cut-off time — but there are strong patterns supported by research.

The Sleep Foundation’s analysis of caffeine and sleep highlights a widely cited study: participants who consumed caffeine even six hours before bedtime experienced significantly reduced sleep time and more nighttime awakenings.

The surprising part is that participants did not always notice that their sleep was disrupted. They didn’t feel “wired.” They didn’t feel “stimulated.” Caffeine simply made their sleep lighter and less restorative. This mismatch between experience and physiology is why cut-off times matter. You may feel calm, but your nervous system may still be processing the stimulant.

Across studies, recommended cut-off windows tend to range from:

6 hours before bedtime for average metabolizers

8–10 hours before bedtime for slow metabolizers

4–5 hours before bedtime as an absolute minimum

Most sleep researchers agree on one thing:

drinking caffeine after 2 PM increases the likelihood of sleep disruption for many people, especially those with variable schedules or sensitive nervous systems.

But this window isn’t a rule — it’s a starting point.

Why “6 hours before sleep” is a guideline, not a rule

The idea of stopping caffeine six hours before bed became popular because it feels relatable: you drink coffee around midday or early afternoon, and by evening, you assume the effects have softened.

But the six-hour guideline is just that — a guideline. It doesn’t account for:

metabolism differences

liver enzyme variability

hormonal influences

circadian rhythm type

stress load

caffeine sensitivity

sleep disorders

medication interactions

And most importantly, it doesn’t account for behavioral context. If your evenings are calm and unrushed, caffeine may linger more noticeably. If your evenings are busy and overstimulating, you may not notice its impact at all — even though your sleep quality still decreases.

Harvard Health’s overview of caffeine and sleep emphasizes that subjective alertness is not a reliable indicator of caffeine’s physiological effects.

This means you may feel “fine” at bedtime, but your sleep architecture still shifts.

Cut-off times are less about how you feel and more about how your system metabolizes stimulation.

How caffeine timing interacts with circadian rhythm

Caffeine doesn’t just affect sleep pressure — it also interacts with the body’s circadian rhythm, the internal 24-hour clock that regulates alertness and rest cycles.

Caffeine can slightly shift this rhythm, especially if consumed later in the day. It delays the brain’s perception of “nighttime,” which is why a late cup can result in feeling sleepy later than usual.

This effect is subtle but meaningful. If your natural rhythm leans evening-type, caffeine can push it even later. If you’re morning-type, caffeine can create a sense of internal “skew,” making bedtime feel off-kilter.

Studies show that late-day caffeine may:

delay melatonin onset

reduce slow-wave sleep

increase nighttime awakenings

shorten total sleep time

The impact varies from person to person, but the direction tends to be consistent. This interaction between caffeine and circadian rhythm also explains why two people can drink the exact same afternoon coffee and have completely different nights.

Slow vs. fast metabolizers: why your friend sleeps fine after an espresso

This is one of the most common questions people ask:

“Why can I’t drink coffee at 4 PM when my friend can drink it at 8 PM and sleep perfectly?”

The answer lies in genetics — specifically, variations in the CYP1A2 enzyme, which determines how quickly your body breaks down caffeine.

Fast metabolizers clear caffeine quickly.

Slow metabolizers clear it slowly and feel its effects much longer.

Slow metabolizers experience more sleep disruption from caffeine — even in moderate doses — because the stimulant remains active deep into the evening.

Fast metabolizers genuinely can drink a late coffee and fall asleep without difficulty. But even fast metabolizers may lose depth of sleep — the stimulant may not keep them awake, but it can still lighten their sleep architecture.

That’s the nuance:

being able to fall asleep is not the same as sleeping deeply.

Many people assume they’re “immune” to caffeine because they don’t feel stimulation. But objective sleep quality may tell a different story.

Caffeine sources people forget about

Most people think of caffeine as something found in coffee. But late-day caffeine can quietly slip into your routine from other sources — sources that feel mild or harmless.

These include:

tea (black, green, white, matcha)

chocolate

cocoa

energy drinks

some sodas

pre-workout and fitness supplements

migraine medications

certain herbal blends marketed as “energy teas”

Even moderate amounts can affect sleep timing if taken in the late afternoon or evening.

This is why cut-off strategies often work best when they consider the entire caffeine landscape, not only coffee.

Finding your personal cut-off time through self-observation

While scientific guidelines offer a helpful starting point, the most accurate caffeine cut-off time comes from noticing how your body responds. Caffeine metabolism is shaped by genetics, stress, hormones, and even the timing of your meals — so the ideal window is personal, not universal.

A gentle way to explore your cut-off time is to begin with a neutral baseline. Start by choosing a day when your schedule feels predictable and your sleep environment relatively consistent. Have your usual morning coffee, but avoid caffeine after midday. Observe how your evening feels, and especially how your body responds when you move toward sleep.

If you fall asleep easily and your sleep feels smooth, try moving your last cup slightly later — perhaps 1 PM, then 2 PM. Notice if anything shifts: not just in your ability to fall asleep, but in the quality of your sleep. Do you feel alert or foggy upon waking? Does your sleep feel deep or shallow? Do you wake during the night?

These subtle markers often reveal more than bedtime sensations alone. Many people report no difficulty falling asleep but discover, through self-observation, that their nights feel more fragmented or less restorative after late caffeine.

If your evenings already tend to be overstimulating — full of screens, bright lights, or high cognitive activity — even small amounts of late-day caffeine can create a fragile internal environment. But if your evenings are calm and grounding, your caffeine window may stretch slightly longer without noticeable disruption.

The key is to approach this process with curiosity rather than rules. Your goal isn’t to eliminate caffeine — it’s to understand your rhythms.

Caffeine’s emotional footprint in the evening

Beyond its biochemical effects, caffeine also shapes evening emotional states. Some people experience subtle irritability when caffeine lingers too late in the day. Others feel slightly more mentally active, even if they don’t feel outright “stimulated.” These micro-shifts can make it harder to engage in evening wind-down rituals that require softness — like gentle reflection, digital twilight routines, or somatic grounding.

A late-afternoon coffee can sometimes create an invisible layer of cognitive brightness. You may feel awake, but not in a way that supports rest — the mind becomes a bit sharper, less spacious. This mental edge can interfere with the natural descent toward bedtime calm.

This doesn’t make caffeine “bad.” It simply highlights how timing shapes internal landscapes. Your last cup sets the emotional tone for the night.

Late-afternoon rituals that replace the “4 PM coffee”

One reason people struggle with caffeine cut-off times is that coffee often serves a purpose far beyond alertness. It can be a comfort, a pause, a boundary in the day, or a small moment of reward. Losing that ritual can feel like losing a piece of your emotional structure.

The goal isn’t to remove the ritual — it’s to replace it with something that offers the same sense of pause without the stimulant load.

Late-afternoon alternatives might include:

a warm caffeine-free herbal blend

a short walk in fresh air

a stretch-and-reset break for the shoulders or hips

a brief moment of sunlight exposure

a grounding breathing pattern

These practices don’t replicate the buzz — they replicate the transition. They support the change in tempo that most people seek in the late afternoon: the shift from momentum to completion.

Pairing these rituals with the evening practices explored in How to do a digital detox evening for better sleep and mental clarity can create a rhythm that flows naturally toward night.

Why caffeine timing matters more than quantity

It’s easy to assume that more caffeine is the problem — as if drinking an extra cup creates sleep disruption. But timing often matters more than total intake.

A strong morning coffee may feel stimulating, but because it aligns with internal alertness cycles, it rarely interferes with nighttime rest. A small late-afternoon tea, however, might have a lingering effect simply because it lands too close to your evening slow-down window.

This is why some people find they sleep better with a single strong morning cup than with two weaker, spaced-out cups. The rhythm is cleaner. The stimulation is front-loaded. The body transitions smoothly through the day.

Quantity matters — but timing shapes the emotional and physiological arc.

Caffeine and stress: an under-recognized interaction

Stress levels significantly alter how the body processes caffeine. When cortisol — our primary stress hormone — is elevated, caffeine tends to feel stronger and last longer. The nervous system becomes more sensitive to stimulants when it’s already under internal pressure.

This creates a subtle feedback loop:

stress makes caffeine more potent

caffeine can amplify tension

tension can delay evening calm

delayed calm feeds nighttime restlessness

During stressful seasons, your caffeine cut-off time may need to shift earlier. Not permanently, but temporarily — as a form of internal care.

Evening calm becomes easier when the nervous system doesn’t enter the night carrying the residue of daytime stimulation.

The cultural myth of “unaffected sleepers”

Most people know someone who can drink an espresso at dinner and fall asleep quickly. This creates a belief that caffeine simply “doesn’t affect” some individuals. But falling asleep and sleeping well are not the same.

Research shows that even people who fall asleep easily after caffeine often experience:

reduced slow-wave sleep

shorter REM periods

increased micro-awakenings

lighter overall sleep

They wake without obvious complaints, but their sleep architecture is subtly altered. Over time, this can create low-level fatigue that people attribute to life circumstances rather than caffeine.

Again, caffeine isn’t the enemy — the story is simply more nuanced than “I can drink coffee after 6 PM and sleep fine.”

The body feels the effects even when the mind doesn’t notice them.

Building a cut-off time that supports your future self

Your caffeine cut-off time is less about perfect alignment and more about creating a rhythm that helps your future self rest. When you choose an earlier last cup, you’re shaping the internal environment you’ll carry into the evening.

A helpful way to frame the decision is:

“How do I want tonight to feel?”

If you want:

a calm wind-down

an unforced evening pace

a smoother emotional atmosphere

an easier transition into bed

deeper sleep cycles

…then choosing an earlier caffeine window becomes a form of self-support.

It’s not about rules. It’s about environment — the internal kind.

Putting it all together: your personal caffeine rhythm

When you understand how caffeine interacts with:

adenosine

circadian timing

evening emotion

stress load

sleep architecture

…you can design a caffeine window that feels aligned with your life.

For many people, the ideal last-cup range falls between 12 PM and 2 PM.

For slow metabolizers, the window may be closer to 10 AM to 12 PM.

For fast metabolizers, it may stretch to 3 PM — occasionally later.

But the most accurate guidance comes from observing your:

evening calmness

sleep depth

nighttime awakenings

next-morning clarity

Your body holds the data long before your tracker does.

Conclusion: your last cup shapes your night more than your day

Caffeine is a beautiful companion — a symbolic start to the morning, a creative spark, a comforting pause. But it’s also a stimulant with a long, quiet tail. Your last cup shapes not only your energy but your evening mood, your sleep architecture, and the softness of your wind-down.

Cut-off times aren’t restrictions. They’re choices that support clarity, emotional steadiness, and a calmer night.

When your caffeine rhythm aligns with your sleep rhythm, you feel the difference — not in dramatic ways, but in subtle ones: deeper breaths, fewer awakenings, a softer mental tone, a morning that feels more refreshed than rushed.

The science matters.

But ultimately, the rhythm you choose becomes the rhythm you feel.